After nearly three years of negotiations, the sixth round of talks on a global plastics treaty concluded on August 15 in Switzerland.

Representatives from 183 countries – including Canada – and more than 400 organizations met to work toward a legally binding agreement addressing plastic pollution across its full lifecycle, from design and production to disposal.

While a final treaty was not reached at this time, the discussions that took place — and the renewed calls for action following the latest round of negotiations — continue to signal a strong commitment to addressing plastic pollution both internationally and here in Canada.

What is the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC)?

These discussions take place under the guidance of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC), a temporary United Nations (UN) body established in March 2022. Its mandate is to develop an internationally legally binding instrument to address plastics across their full lifecycle: from design and production (upstream) to use, recycling, and disposal (downstream).

The INC was originally tasked with completing negotiations by the end of 2024. However, the fifth round of talks in December 2024, known as INC 5 in Busan, South Korea, ended without consensus. As a result, the UN scheduled an additional session, INC 5.2, held in August 2025 in Geneva, Switzerland. After ten days of discussions, representatives were unable to reach agreement, reflecting differing priorities between countries pushing for limits on plastic production and those preferring a narrower focus on waste management and recycling.

With no agreement at INC 5.2, questions remain about whether there will be another negotiating round (e.g., an INC 5.3). But regardless, momentum on addressing plastic waste and pollution continues to build given growing linkages to its impact on human health and the environment.

Where Does Canada Stand?

As a founding member of the High Ambition Coalition to End Plastic Pollution– a group of ambitious countries committed to ending plastic pollution by 2040 – Canada has positioned itself as a supporter of a comprehensive global treaty on plastic pollution.

In the Government of Canada’s Statement on the conclusion of INC-5.2, Environment Minister Dabrusin stated:

“Addressing this issue is complex and requires a comprehensive, system-wide approach to drive the lasting change necessary to end plastic pollution… Domestically, we are implementing a comprehensive plan to reduce plastic waste and pollution, promote a circular economy for plastics, and foster science, innovation, and transparency.”

The statement reiterates Canada’s commitment to securing an ambitious and effective global treaty that addresses the entire lifecycle of plastics. Coupled with its Zero Plastic Waste Agenda, which includes policies to reduce single-use plastics, this underscores Canada’s goal to move toward a more consistent and harmonized framework for reducing and managing plastic waste.

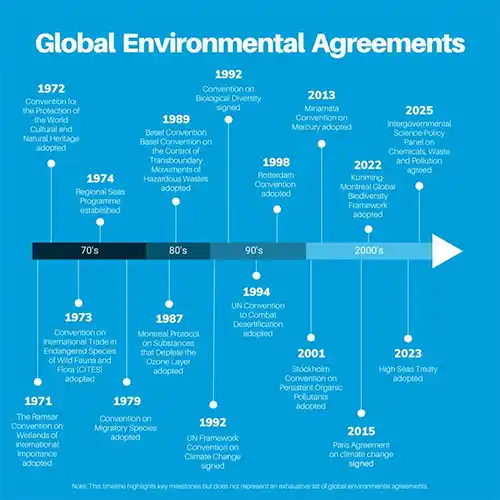

Canada’s role in the plastics treaty negotiations builds on a long history of multilateral environmental agreements, that demonstrate how global cooperation can tackle complex challenges.

Understanding Global Treaties

Global agreements like this are not easy. They take years of debate and multiple negotiating rounds before consensus can be reached.

Take the Montreal Protocol as an example. Following the 1985 Vienna Convention on the Protection of the Ozone Layer, governments reached agreement on the Montreal Protocol in two years, after two rounds of negotiations. The treaty went on to become one of the most successful environmental agreements in history: it was ratified by 197 countries, phased out 98% of ozone-depleting substances, and has led to the gradual recovery of the ozone layer.

But the global plastics treaty feels different. It has already taken over three years and six rounds of negotiations with no consensus. Unlike ozone-depleting substances, plastics may be more complicated: there are hundreds of polymer types, and plastic materials are deeply embedded in modern economies, supply chains, and daily life. Add to that the rise of consumer convenience culture — online shopping, takeout, food delivery, meal kits, pre-cut produce — and plastics have become pervasive in how goods are produced, transported, and consumed. These realities make developing a global treaty more challenging.

Progress is further complicated by industry resistance, particularly from oil- and plastic-producing nations, which continue to argue for a narrower treaty focused on waste management rather than limits on production. This divide helps explain why negotiations have been slow.

History shows that global agreements can be powerful tools for environmental action, but today’s landscape is more fragmented and challenging than in the past. While a binding plastics treaty could provide clarity, alignment, scaled solutions, and avoid a patchwork approach, progress will ultimately depend on depend on coordinated action across governments, industry, and society.

Implications for Canada’s Packaging Sector

Whether a global plastics treaty ultimately succeeds at some point in the future, the negotiations carry important implications for Canada’s packaging sector.

For paper packaging, and for all packaging sectors, how an ultimate treaty defines responsibilities for managing materials, and whether it focuses on production limits, waste management, or both, could have implications across global recycling systems and policy frameworks.

As governments and industry continue to look to shift away from plastics, paper packaging may be viewed as an important alternative given its high recyclability, prominent use of recycled content as feedstock, and alignment with circular economy models.

That said, packaging in general will likely continue to face scrutiny due to the potential environmental and health impacts associated with its production, use, and end-of-life management.

The ongoing debate over the plastics treaty illustrates a broader truth: packaging is not just a materials issue, it’s a system-wide challenge. For paper packaging, this means remaining proactive, transparent, and committed to circular solutions, regardless of how international negotiations unfold.

Conclusion

While the sixth round of negotiations did not deliver a plastics treaty, the work is not over. Canada has reiterated its commitment to a global agreement, and whether or not a treaty is ultimately reached, reducing and managing plastics remains a pressing global priority.

History shows us that international agreements like the Montreal Protocol can provide the structure and clarity needed to drive real change, but they also take time, and today’s context is different. Unlike the ozone challenge of the 1980s, packaging and plastics are now deeply embedded in everyday life, from e-commerce to takeout, making scalable solutions more complicated.

As we await next steps, it is clear that the absence of a binding agreement at this time is not an excuse for inaction; industry leadership, innovation, consumer action, and responsible policies must continue to drive tangible improvements in the sustainability of packaging.

Rachel Kagan

Rachel Kagan

Executive Director

The Paper & Paperboard Packaging Environmental Council (PPEC)